Art Bierman helped lay the foundation for the last 50 years of San Francisco, and you can see it on the ground. There’s no road paved over the Panhandle, because he helped the freeway revolts succeed in the 1960s.

We were lucky enough to sit with Bierman, now 90, at his house in Russian Hill and receive a first-hand account of his involvement in these two pivotal roles. He also has some words of wisdom about the changes happening in San Francisco today.

But first, a little background. Bierman helped to define progressive San Francisco, but his sense of justice and ability to connect with normal people can be traced back to his Midwestern roots.

But you can also see the difference he’s made for the nation.

A faction of Congress had been smearing citizens with the charge of “Communism” for decades through the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1959, HUAC had set their sights on 140 California teachers, some of whom lived in San Francisco. He led an opposition against their subpoenas, an act that set the tone for the protests against City Hall’s infamous “Black Friday” hearings in 1960.

These protests, and a violent police response, pushed the committee out of the city, and caused Americans everywhere to question its repressive goals. Within a decade, HUAC had become a joke, and San Francisco had become known for successfully pushing progressive policies.

Phiz Mezey / San Francisco Chronicle

Born in a small town in rural Nebraska in 1923, he carved himself a path from farm life to urban living in a way you don’t hear about too often these days. He left Midland Lutheran College in Fremont, Nebraska in 1943 to become a Navy pilot, but World War II ended before he saw combat. He returned to Fremont and got married to Sue Reynolds (better known as Sue Bierman, in the world of San Francisco politics) but his time in the Navy, and a host of summer jobs out West beforehand, had given Art an itch to see the world.

Shortly after his return to Fremont, he hitchhiked to Ann Arbor because he heard they had an excellent law program at the University, and in a sign of things to come, walked into the school and talked his way in on the spot. However, he found that he disliked studying law and ended up pursuing a graduate degree in philosophy instead. He was still working on it when the itch landed him in San Francisco in 1950, a place where he had vowed to live after spending time there a decade beforehand.

Now with a wife and child to support, he made ends meet at first by selling Heinz products. But during a lunch break one day in 1952, he walked into the philosophy department of San Francisco State (back when it was still downtown), and met professor Alfred Fisk. The conversation got him a teaching job that over the course of 31 years turned into a professorship – and positioned him to make a big local impact.

Hoodline: What was your greatest contribution as an activist in San Francisco?

Art Bierman: “Beating the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC] in 1959. I saved America! [laughs] Everyone was afraid of them and I took them on. I took an entire summer, a time when I normally didn’t work because I was teaching. [The committee] came out and subpoenaed elementary and high school teachers in San Francisco and a friend of mine, Herb Williams, came to me and said the people who’d been subpoenaed were going to a meeting out on Lake Street.

“We went there and teachers were assembled. They were not well organized, they were scared, and they didn’t look like they had the capacity to show resistance. The fear froze people. My friend told me that these people couldn’t take care of themselves because they were the accused, and that we had to do something. Herb always had good ideas, but he was a low-energy guy…so I said we have got to organize a committee to get opposition going. I talked to few people about joining an organization.

“We met at my friend’s house, which was the locus for the organization, which we called San Franciscans for Academic Freedom in Education, or “SAFE”. I got some lawyer friends and a lot of teachers and other people who were active in the community to make calls to get the word out. We got some stationary with our name on it, too. Our first target was the San Francisco Labor Council.

“I had already started a local AFT [American Federation of Teachers] at San Francisco State, and Herb was our rep to the Labor Council. We asked George Jonas, the Secretary Treasurer of the San Francisco Labor Council—at that time the Secretary Treasurer was more influential than the President of the Labor Council—I asked him if some people were interested in supporting the subpoenaed teachers and he said that he couldn’t pass a resolution that says they don’t want the HUAC to come to San Francisco, but he could get something passed that says the labor unions should look into it, and he got it passed….

“…Philip Burton was then a congressman and probably one of the smartest people I’ve ever known. He was terrific. He said, ‘we’ll go to the local union meetings and we’ll go and talk to them’. He would go into these meetings where the officers were and he’d introduce me to them and tell them what I was doing. Most of these people were anti-communist, many of them coming from places where communism had ruined their lives. However, he told them that these people were trying to take away their freedom. My pitch was that the HUAC was coming to California, but we already had our own laws and why couldn’t we take care of ourselves?

San Francisco Chronicle

"I also pitched the Junior Chamber of Commerce, probably the most conservative group at the time without being fascist, and they bought it too…they even asked me to write an article for their publication. There was also a mayoral election going on, and I asked the two campaign managers how their candidate felt about HUAC investigating San Francisco teachers… I wouldn’t tell them what the other said and they both ended up coming out against it….

“My final target was Bishop Pike, the Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the area…I asked him if he liked these people coming here, and he assigned one of his canons to follow what I was doing and report back to him. I later learned that he had asked the FBI to check on me....

“….So the committee was coming out in a couple of days. [The Bishop] called me up and had me come to his office. He told me he made up his mind what he was going to do, but wouldn’t tell me and said I had to read it in the papers. The next morning, at six o’ clock, my friend Frank Grann called me and said, ‘Art, you won. The Bishop came out against the committee coming.’ Afterwards, the HUAC cancelled. It had never happened before.”

“It was a pretty dramatic meeting the next morning at the Board of Supervisors. Hal Dunlevy, a polltaker, had claimed that he had taken a report that the project would not be a major disturbance to the city and its residents. I took one of his employees, June Dunn, and said, ‘I’m coming over,’ and we invented an entire poll, making it out of total cloth, because I knew that Dunlevy had done the same thing—but ours was more accurate. We were at the Board of Supervisors and [Dunlevy] was furious. ‘You made it all up!’ he shouted. And I replied, ‘That’s right! So did you!’

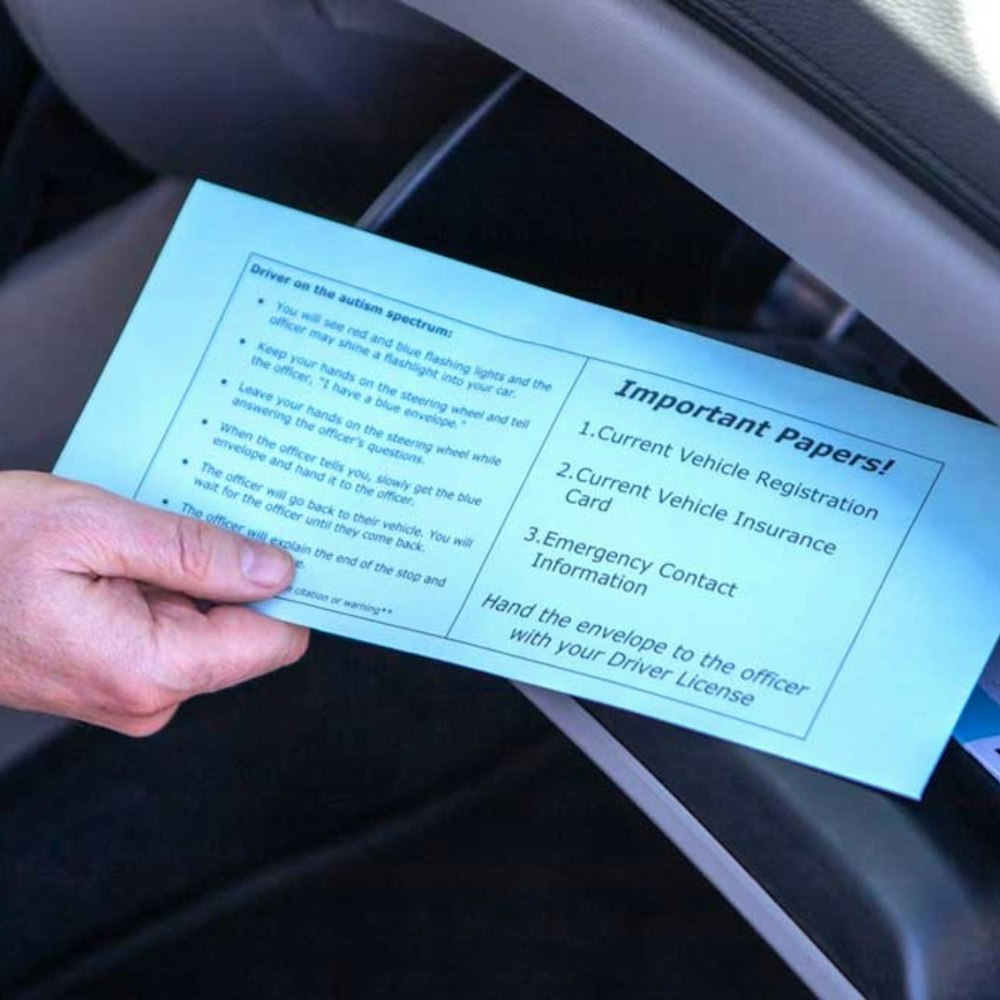

Hoodline: Although the city was safe from anti-Communism for the moment, the HUAC returned the next year in full force, conducting hearing in the second-floor supervisors City Hall chambers on Thursday, May 12th, 1960. The subsequent protest, known as “Black Friday”, resulted in protesters camped outside the chamber doors getting literally hosed down the marble grand staircase and taken to jail (photo above). There was a national public outcry, and an early sign of the anti-government protests later in the decade. And HUAC hearings were never again held outside of Washington, D.C.

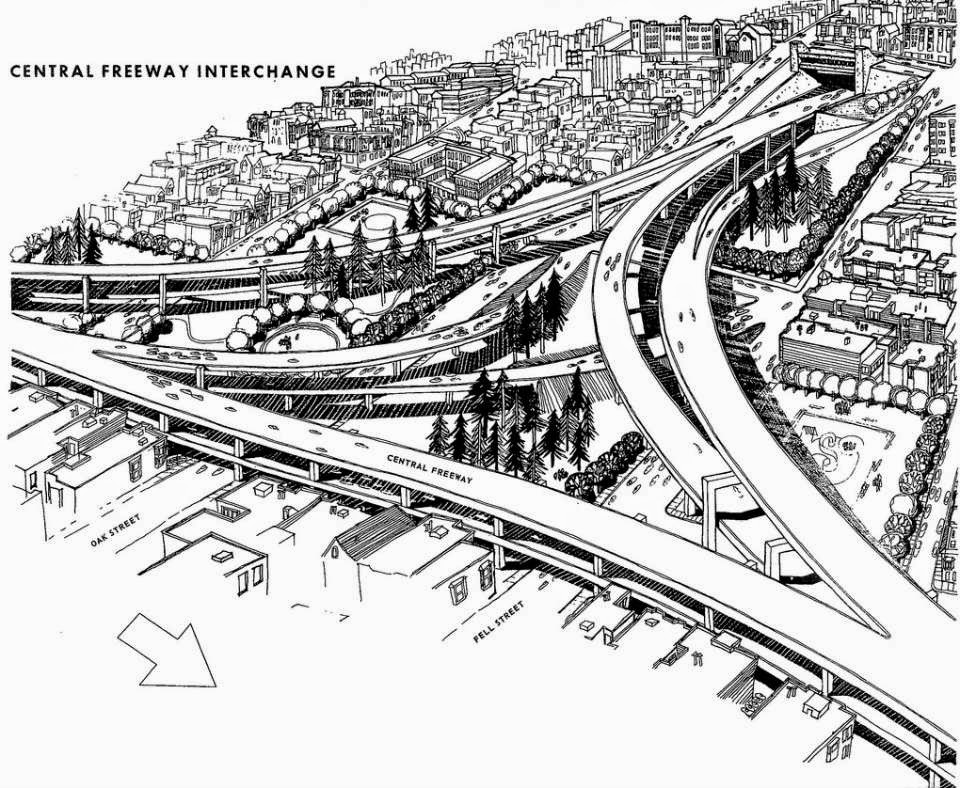

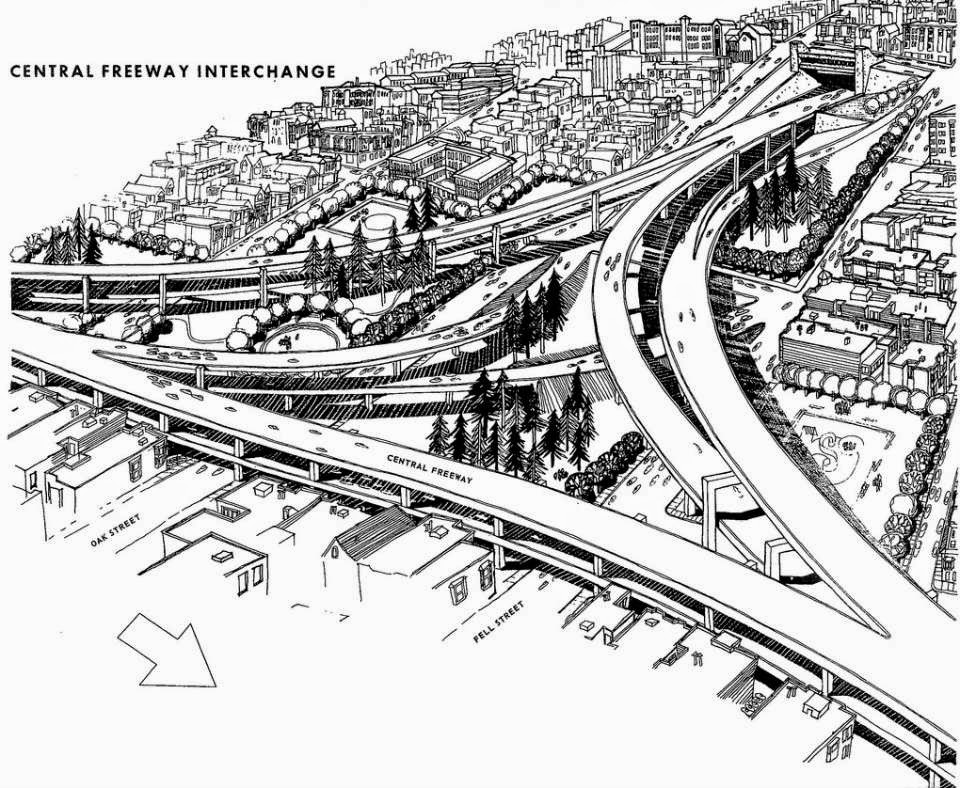

But Bierman was back fighting national forces almost immediately. The Eisenhower administration had created the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s, and planners in California and San Francisco merged this grand scheme with decades of existing plans for paving highways through the city.

We recently covered an older effort to create a "divisional” highway along Castro and Divisadero in the 20s and 30s, that would have gone all the way to the new Golden Gate Bridge. That idea had stalled out as the 101 and 280 were developed further east, but the car-oriented thinking of the era still called for a freeway to connect downtown with the bridge.

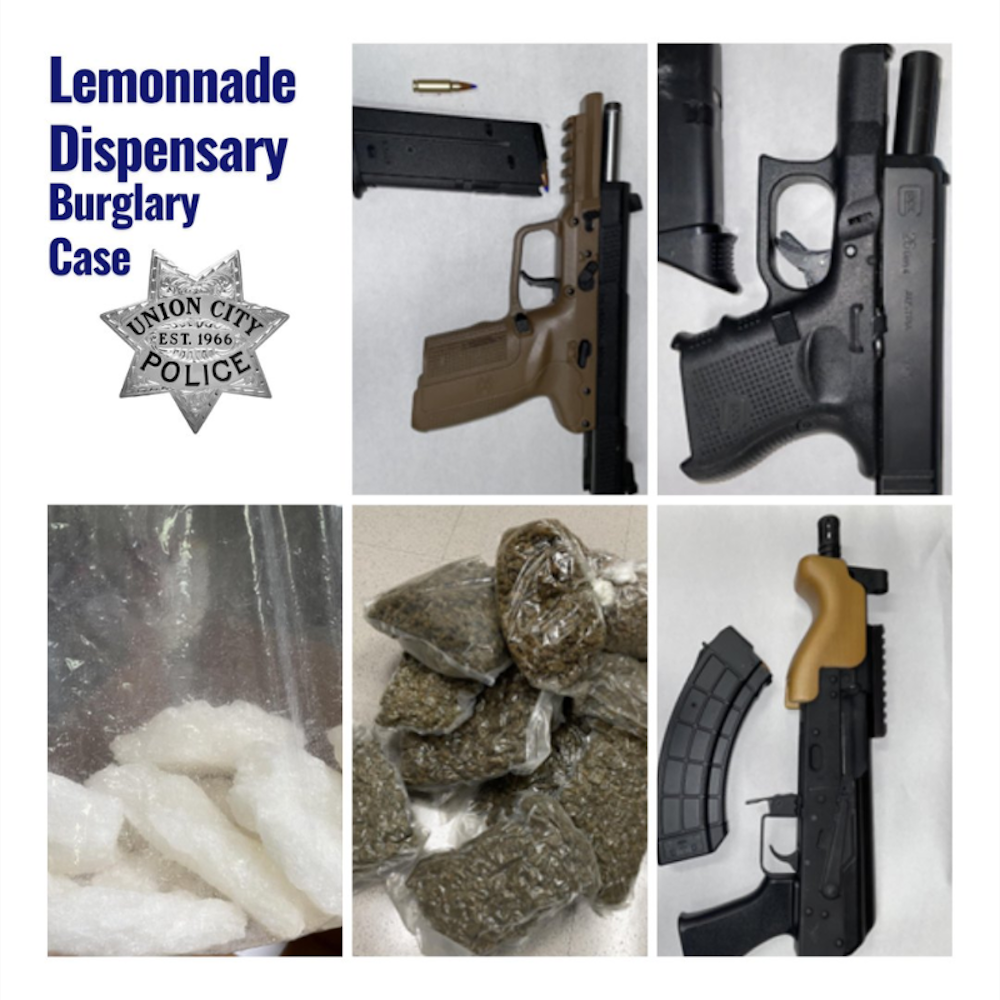

SF Department of City Planning

The catch: the plan called for bulldozing the parks and housing all the way along Oak and Fell between Hayes Valley and Fulton at Park Presidio.

While the city government had already cancelled other freeways by 1959 due to popular outcry, the so-called Panhandle (or Western) Freeway plan was kept alive for the bridge connection.

Art and his family were living in the Haight-Ashbury area at the time and Sue helped create the Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council to advocate against it starting the next year. The couple would go on to take central roles in the fight in the following years, as the issue was debated through the city government. While Sue and the other leaders deserve credit, Art played a hand with his characteristic human touch.

Hoodline: Describe your involvement in the protest against the proposed Panhandle Freeway.

Art Bierman: “We were pretty early environmentalists…The Gellert brothers had built most of the houses along 19th Street and they wanted to cut down Sutro Forest and turn it into a housing development and we had fought them against it. Adolph Sutro had deeded the forest to the city and the Gellerts were trying to get the supervisors to give it up. We got the Board of Supervisors to reject it. Sue and I were pretty deep in the Burton Machine [a San Francisco political coalition prominent in recent decades], which included Willie Brown, George Moscone, Diane Feinstein, and Philip and John Burton… Also, Governor Brown and the District Attorney, Thomas Lynch, had houses built against the entrance of the forest. Lynch’s wife was a powerhouse and she knew everybody. We organized the thing, but she had the heavy balls that crashed into the Gellert Brothers’ plans.

“That was a prelude that put us into the game of environmental protection. We also knew most of the people on the Board of Supervisors at the time. The city had to give the federal government permission in order for them to destroy the city’s streets and create a highway to go through the panhandle. They also needed permission to destroy the Panhandle, the north east part of Golden Gate Park, and Park Presidio, including houses on either side of all of those areas.

“The people who lived on the sides of Park Presidio were very conservative and very rich, and it was easy to convince them to not let them destroy their homes. The one holdout was a liberal on the Board of Supervisors, Jack Morrison, who was a very terrific and thoughtful man. He had decided he was going to vote for [building the highway], and once he got behind something, he could be very stubborn.

Flickr / WalkingSF

“On a Sunday morning, I got a call from Jane, his wife. The vote was going to be the next day, on Monday. She told me that Jack had actually never seen the route and what would be lost. She said, ‘come pick us up and take a ride on the route. All he’s seen are the drawings. And don’t bring Sue, because they’ll get into an argument.’ I went over, picked him up, and none of us said anything. We just wanted him to look.

“Just before the tunnel that goes into Park Presidio, we looked over to the right and the was a little playground with children playing on it and I said, ‘why don’t we go take a walk there, just down to the right before the tunnel,’ and then I took him home. He called me later and said he changed his mind, but not to tell Sue. ‘Mums the word,’ he said.

“Another important part of this was the fact that a new law was eventually passed that required more detailed environmental reports to be done in situations like these.”

Hoodline: We’ll add that the freeway revolts also convinced the public to vote to fund BART’s construction around the same time, and generally heralded the transit-first policies the city has been (more or less) following ever since.

Sue also went on to a career of public service, culminating with her election to the board of supervisors in 1992. She and Art eventually separated, but remained on good terms, and she tragically died in a car crash eight years ago.

Today, Art continues to lead an inspiring life. Happily re-married to poet Kathleen Fraser, he writes philosophy, translates Italian literature to English, spends half of the year in Rome, makes excellent martinis, and is considered by some to be one of the best landlords in the city . With so much perspective, we decided to get his two cents on the current state of San Francisco.

Hoodline: What is your take on San Francisco’s recent tech bubble? How has it affected the city?

Art Bierman: “I don’t know if it’s a bubble. I think it’s here to stay. These people make things, they are like the old industrialists. Those people made things and we [San Francisco] are like the factory for the electronic age. To give a philosophical take on it, Heraclitus’s tagline was ‘panta rei,’ meaning ‘everything changes.’ If a city prospers, why would you argue about the change? You must always welcome the new, just so long as it’s not Hitler or something. Let’s put it this way: I’m glad there’s not dinosaurs out to eat me anymore. That, to me, was a welcomed change.

“The people coming are children. They have to grow up, but everyone needs to do that. They are uncultured, but they are smart and everyone can learn to live better.”