Shrouded in fog and densely studded with eucalyptus trees, Mt. Sutro is the Inner Sunset’s most prominent natural landmark. Despite the neighborhood’s ongoing evolution, it’s clear why the city’s third-highest hill has been used for a university hospital, a Cold War missile battery, and until 1934, a commercial lumber operation.

courtesy San Francisco Public Library

After cashing out his Nevada silver mining holdings in 1879, German engineer Adolph Sutro moved to San Francisco and began acquiring large tracts of real estate. At his peak, Sutro owned as much as 10 percent of the city, including Land’s End, Mt. Davidson and what was then known as Mt. Parnassus, a sand dune covered with native grasses and shrubs.

Sutro used his wealth to create attractions like the Cliff House, Sutro Baths, and critically, infrastructure that connected his new western neighborhoods with the rest of the city. During his tenure as Mayor, he donated 15 acres to Affiliated Colleges of the University of California to create what’s now known as UCSF’s Parnassus campus. He also had thousands of eucalyptus trees planted to the west and south of present-day Mt. Sutro, extending at one point all the way to Monterey Boulevard.

This large-scale forestry operation used a nursery near Laguna Honda as a research and development facility. Sutro’s tree-love led him to kick off the state’s first Arbor Day in 1886, but historians note that forested land within city limits also received substantial tax breaks. Whatever his reasons, however, Sutro had created a dense forest of blue gum eucalyptus, Monterey pine and Monterey cypress atop the hill that would bear his name.

By 1889 the nursery at 1000 Clarendon had 250,000 plants, where different species were evaluated for their ability to thrive in sandy soil. Blue gum eucalyptus was the leading selection, which is why these trees now comprise 80 percent of the population. According to reports of the day, plantings were managed by teams of workers whose efforts were complemented by arboreal-minded residents and schoolchildren.

San Francisco Call, 4/30/1909

When Sutro died in 1898, he left behind a land-rich, cash-poor estate and kicked off years of legal battles and squabbling among his heirs. In 1909, a deal was announced between the Sutro estate and Consolidated Eucalyptus Co. to log and process trees across 1,538 acres. The company cut only the eucalyptus trees, which were then calculated at numbering 1,000 trees per acre.

Despite the fact that it was sandwiched between a college campus and a residential neighborhood, Mt. Sutro's bounty of timber was harvested for years. The trees grew quickly and were chiefly processed to make paper products and oil, which stores so much energy that eucalyptus are known to explode while burning.

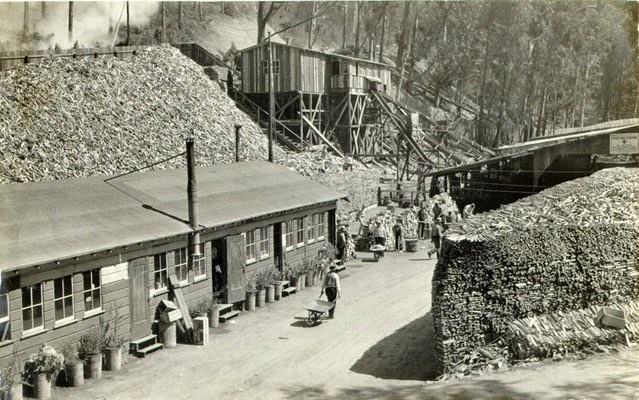

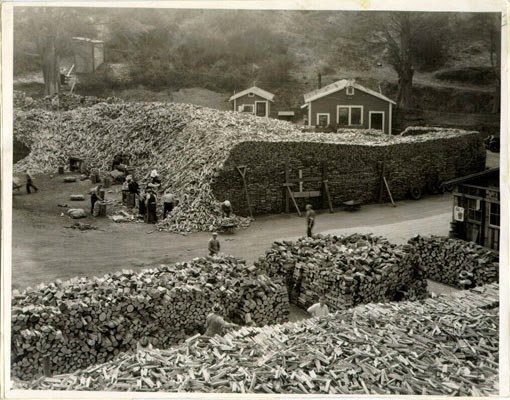

Here's a peek at the Sutro forest wood yard in 1934:

via San Francisco History Center, SFPL

via San Francisco History Center, SFPL

Logging continued intermittently until October 15, 1934, when a 10-acre fire fanned across the hillside (pictured below). After it was controlled, locals lost their taste for a backyard lumber mill, and operations ceased until they were briefly resumed during WWII.

via San Francisco History Center, SFPL

Fast-forward to the current century, when Mt. Sutro's forest saga continues. In 2009, controversy erupted after UCSF applied for a federal grant intended to reduce fire risk by removing most of the century-old eucalyptus forest, replacing it with less flammable native plants. After massive opposition from neighborhood groups, UCSF withdrew the grant application and launched a long-term environmental impact study.

Today, the Mt. Sutro Open Space Reserve consists of 61 acres that are the property of UCSF and 19 acres owned by the city. Miles of foggy trails lead hikers and cyclists through an idyllic forest populated by Great Horned Owls, hummingbirds, and pungent trees that top out above 100 feet. Explorers are free to visit the former Nike missile installation and keep an eye out for the 45 species of birds who call these woods home, but there's virtually no evidence of San Francisco's last lumber camp.